Lean Grants & Contributions Case Study

74% reduction in processing time + 300% increase in morale

Summary: A federal government department used Lean thinking to transform its grants and contributions process to reduce a 24-week cycle to just seven weeks, without anyone working harder, and increasing staff morale by 300%. Funding applicants this much quicker gave them more time to implement programs, delivering more value to the target communities.

The Government of Canada transfers millions of dollars every year to a wide range of entities in the form of grants and contributions. To give you an idea of the scope of these types of payments there were 85,594 in 2018 broken down by size as follows

Less than $10,000

$10,000 - $25,000

$25,000 - $100,000

$100,000 - $1,000,000

$1,000,000 - $5,000,000

More than $5,000,000

39,990

14,173

14,514

13,948

2,186

783

Source: Government of Canada https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/432527ab-7aac-45b5-81d6-7597107a7013

By any measure, those are some big numbers. It could be argued that they are also some of the most important because they represent a source of funding for a long list of worthy organizations and programs that do everything from help develop innovative technologies, support socially responsible community initiatives, promote diversity and more.

But consider this. Every organization who received a payment had to apply, was evaluated, approved, paid and was followed-up with to ensure accountability. It’s impossible to say how many organizations applied but weren’t approved but it’s safe to assume that between the two, managing grants and contributions is a massive undertaking. Managed well, thousands of well-deserved initiatives get funding. Managed poorly, programs are delayed, people and businesses suffer and, sometimes, it ends up in the news.

This is the story of one federal government department who wanted to improve how they delivered grants and contributions.

The department was faced with this situation: it had a 24-week service standard to respond to applicants, which it generally met but not without employee heroics and frustration. It also had to deal with complaints both from its proponents and the Canadian government. Applicants reported that delays in responses to funding requests negatively impacting their ability to plan and run programs, and that its funding program requirements were unclear. The Canadian government – this organization’s “boss” – was pressuring the department to reduce its service standard to 10 weeks, which was at the time was viewed as “impossible”. Employees felt caught in the middle, resulting in increasing levels of stress and tension, as well as a feeling of being under-appreciated.

To address the problem, the organization ran a 1/2-day training on Lean fundamentals and a 5-day improvement workshop. The goal was to document, fully understand and identify blockages to “flow”, with a view of removing non-value-added activities embedded within the application process from all perspectives: applicants; employees; and management. The objectives were to: (1) reduce delivery time by 50%; (2) reduce stress and frustration both amongst applicants and employees; and (3) free up employee time to allow them to better connect with and understand their applicant's needs.

The approach is rooted in the principle that a bad process beats a good person every time. However many employees are willing and even passionate about doing what is best but without the right support and structure this is difficult at best and sometimes even impossible.

The other fundamental reality is that processes are often invisible. How often do staff do non-value-added work just because they are just trying to keep their heads above water? And who really understands both the end-to-end goal of the organization and how to contribute to it? For all the procedures, guidelines and practices used in day-to-day work, what is the “job” it is intended for – and how effectively is it accomplished? Often the answers to these questions are less than satisfactory.

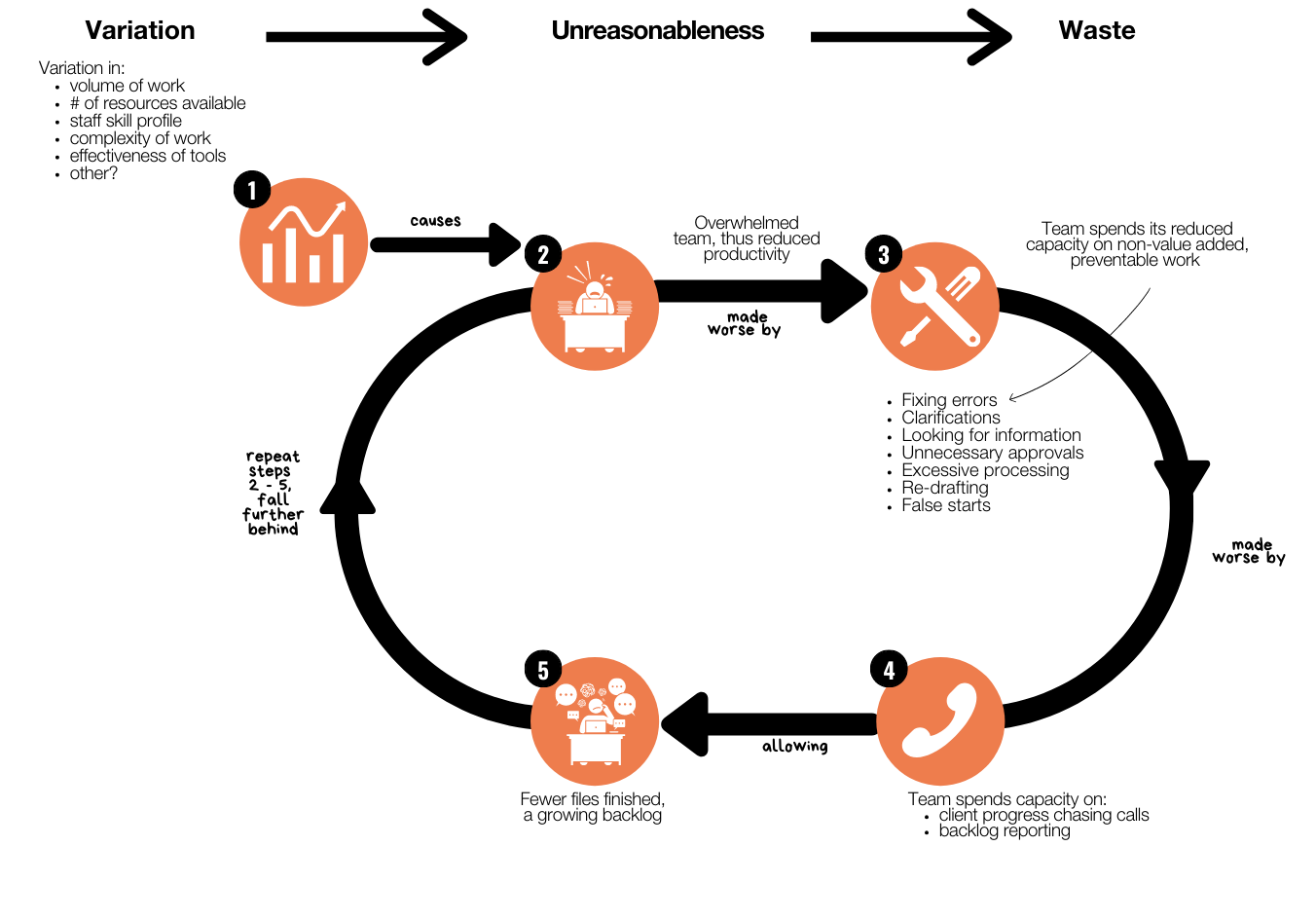

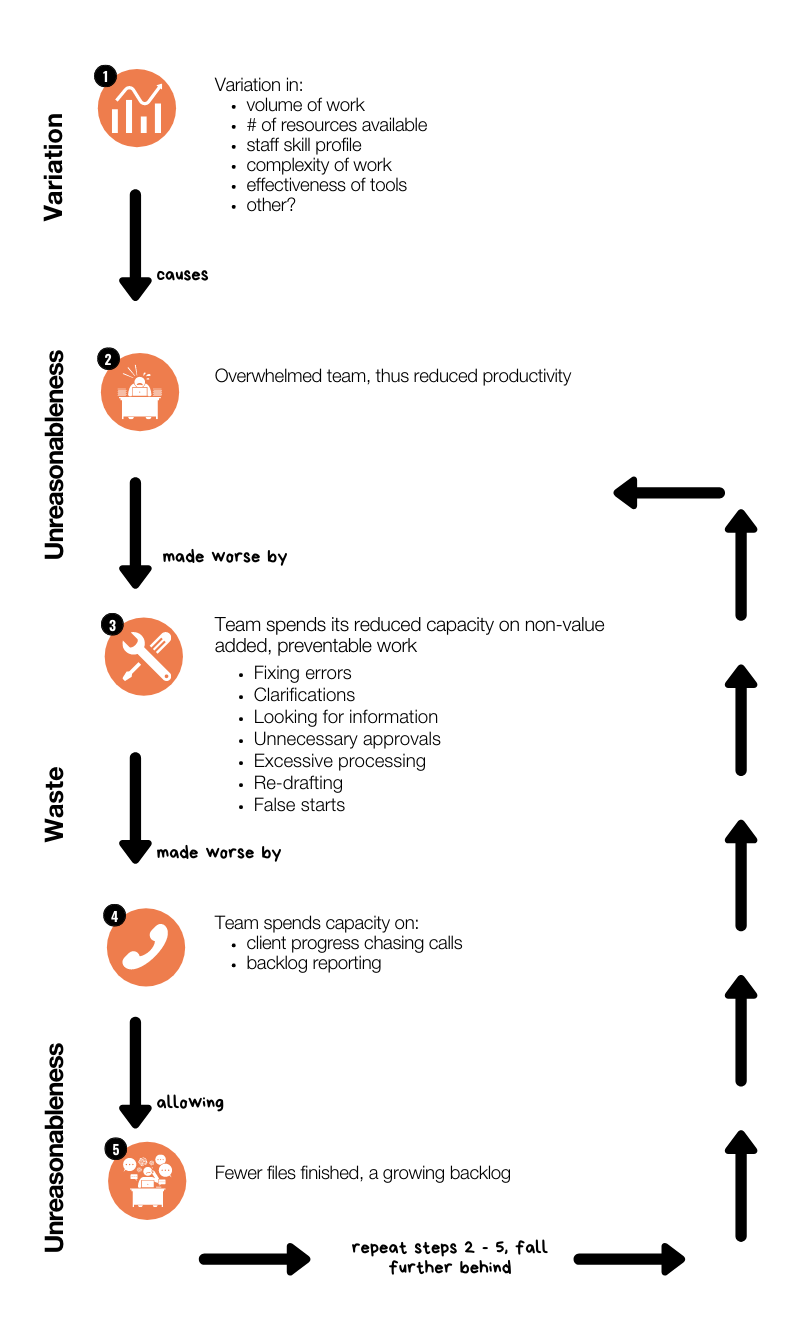

A system of work often suffers from a chain of events that reduces productivity and slows down delivery to clients, creating overwhelm and frustration as seen in the diagram below. Looking at how a backlog develops illustrates this.

The first step is to understand what the current process really is. Not what it is supposed to be or what people think it is; but what it really is. How? Get the right people in a room and map out the process out using unabashedly low-tech white boards and sticky notes. This in itself is often a revelation to the participants. More importantly, it sets the stage to collectively identify major pain points, which can be analysed in more detail to uncover the root causes of these issues and ultimately develop potential counter-actions to address them.

After completing this phase the organization identified five fundamental interruptions to flow:

- Unclear management expectations

- Overlapping funding submission dates

- Poor quality of submissions

- Multiple review loops

- Inadequate people and priorities management

So basically, there were three problem areas: (a) structural, in how the organization established conflicting submission dates leading to overwhelm; (b) lack of trust between management and employees, mainly due to unclear expectations; and (c) unclear and inadequate communication to applicants. This required partial solutions from all stakeholders: applicants; senior management; middle management; and employees.

To fix the problem the team came up with the following solutions:

- Stagger submission dates where possible: while one-off projects still needed to be reviewed in batches because of limited funding availability – and hence a fixed submission date – requests related to on-going, multi-annual projects could be spread out over the year

- Revisions to content and standardized use of tools: if everyone is working with the same tools, there is greater clarity on what is required and, by extension, more homogeneous conclusions and recommendations.

- Review roles and responsibilities: applicants apply; analysts analyze; and management approves. Sounds simple, but often these roles become blurred where there is lack of clarity and/or trust.

- Training, both for applicants and employees: changes to processes alone are rarely successful without adequate training. It is, after all in this knowledge age, people who make things happen

- Develop a more trusting environment: in many ways an outcome of the first three solutions, but extremely important. Good quality applications result in better and more efficient analyses; better analyses result in less management intervention; less management intervention results in more employee empowerment. More trust and a whole lot less work for everyone! Stephen M. R. Covey talks about a “trust dividend” in his book The Speed of Trust: as trust goes up, speed goes up and costs go down.

Impact: A slow, heavy process results in an even slower, heavier process.

Because the above challenges slowed the process to a crawl, a set of problems that happen almost uniquely to slow-moving work often made the process go even slower. Following are some problems that happen to 5-month-old (or older) files that do not typically happen to 7-week-old files:

- Management has time to reconsider how the program works, so changes mind on scope and details = redrafting, re-approving documentation.

- Overtaken by events – the situation and requirements change = the program needs to be significantly re-written and re-approved, or cancelled, wasting the effort invested to date.

- Turnover in staff – staff leave and are replaced = the program spends time onboarding new staff instead of delivering the programs

- “Where’s My Stuff?” / Progress-Chasing – A 7-week file requires little status updating or progress reporting back to the applicants. The slower the file, the more effort the program spends responding to status inquiries, and providing progress reporting = the program spends time on status updating and responding to inquiries instead of doing the work that is the subject of the status update/inquiry.

Results: The results have not only been significant, but lasting and cumulative. And more importantly, home-grown without the need for an external facilitator. They include:

After nine months (March 2016)

- A 92% improvement in the speed of applications as measured by the time required to process them. Pre-workshop, the average processing time was 19 days due to the need to clarify/augment the information submitted. Nine months later, processing time was 1.5 days

- A 50% reduction in the time required for management approval – from 23 days to 11.5 days

- A 64% reduction in turnaround time within the department – from 21 weeks to 7 weeks

- A 50% reduction in overall response time to the applicant (including the most senior level of approval) – from 27.5 weeks to 13.5 weeks

- Increased employee morale from 1/5, to 4/5 as measured by an internal barometer.

After 23 months (April 2017)

- Effective approval levels pushed down to lower levels, made possible by reduction in errors and targeted employee training. While not measured explicitly, anecdotally this reflects a higher level of trust within the department

- Streamlined consultative processes

- A multi-tiered analysis approach based on file complexity and issues vs a one-size fits all, reflective in the reduced turnaround time and management intervention

- A further reduction in the overall response time to applicants from 11.5 weeks in March 2016 to 10 weeks in April 2017

- An increasing and sustained continuous improvement mindset and utilization of tools, techniques and principles such as visual management, stand-up meetings and pro-active learning.

Because the above challenges slowed the process to a crawl, a set of problems that happen almost uniquely to slow-moving work often made the procurement go even slower. Following are some problems that happen to 3-to-5-month-old files that do not typically happen to 3-week-old files:

- Client has time to reconsider, so changes mind on scope and details = redrafting, re-approving documentation.

- Overtaken by events – the client’s situation and requirements change = the RFx needs to be significantly re-written and re-approved, or cancelled, wasting the effort invested to date.

- Turnover in clients – clients leave and are replaced = Procurement spends time briefing new clients/stakeholders to get them up to speed.

- “Where’s My Stuff?” / Progress-Chasing – A 3-week file requires virtually no status updating or progress reporting. The slower the file, the more effort Procurement spends responding to status inquiries, and providing progress reporting = Procurement spends time on status updating and responding to inquiries instead of doing the work that is the subject of the status update/inquiry.

-

The Improvement Approach

The team and its leaders engaged Lean Agility to guide them through a multi-step 20-day improvement project. They chose this approach to maximize the buy-in and to ensure that the analysis and solutions would increase their chances of success compared to a superficial, hasty exercise that provides solutions that don’t solve the key issues, and don’t get implemented.

- Project Charter:

- Define the problems to be solved, objectives, constraints (e.g., can’t spend money on a new digital system, or hire more people – solve the process issues first). Create a project plan and protect the core project team from daily work so that they can focus on the project and get quick results.

- Identify a small group of knowledgeable Procurement Specialists and clients to engage with as a core project team. In this case, the IT department was the biggest, most-motivated client – they signed on to this journey with two key Procurement Specialists and their manager.

- Map the Process:

- Gather data on the current process – how long do different types of files typically take from start to end? At each major process phase? What types of errors do clients most often make? Which months are the highest intake months? Why? How can high seasons be managed/influenced?

- Create a value stream map of the current process, for a specific, important type of file. In this case, focusing on the path taken by a $100k+ Cloud Software competitive purchase process was the one that the sponsors expected would teach the organization the most about its procurement processes in general.

- Analyze the Process:

- Seek to deeply understand the root causes of why the process underperforms. For example:

- Why are peak months so busy? What can be done to level out the work? [Hint: poor or no planning]

- Why do clients submit documents that are unclear and that require so much back and forth [Hint: the forms and tools are designed by Procurement experts using expert language, not for busy, distracted managers who might only use the process once per year]

- Why do the document reviews take so long and consume so much effort? [Hint: they’re done in slow motion, and rarely do the stakeholders get together face to face to collaborate in a “one-and-done” fashion.]

- Seek to deeply understand the root causes of why the process underperforms. For example:

- Create and Quickly Try Out Solution Experiments that are likely to solve the key issues:

- Treat solutions as “experiments”, by trying the new idea out on a handful of files, then doing a quick retrospective to learn what works and what does not, and then quickly trying another iteration, creates an evidence-driven, fast, way to improve a process. Plus, getting senior management approval to try an “experiment” on a handful of files is often 80% faster than asking for the green light to completely change a process (without providing any evidence that it will work) – requiring less governance to negotiate resulting in faster implementation.

- Create psychological safety – treating the solutions as experiments means that the emphasis is put on learning what works, and stumbling, but then adjusting/fine tuning to quickly solve the problem. This helps create a culture where it is comfortable, and even expected, to try new ways of working.

- Create a visible project plan and regular improvement meetings. Carving the time out of the daily work to do this is critical to implement improvements that work, and to build a culture where improvement is part of how the work is done.

- Ongoing Continuous Improvement

- Create a simple dashboard that measures the health of the process and continue running regular improvement huddles so that the team adjusts to new challenges. It is hard to manage what you cannot see. Some examples of what a dashboard might show:

- Where is the work piling up?

- Who is overloaded?

- What kind of errors are we seeing?

- What new work will be coming into the pipeline?

- Create a simple dashboard that measures the health of the process and continue running regular improvement huddles so that the team adjusts to new challenges. It is hard to manage what you cannot see. Some examples of what a dashboard might show:

-

Reflections on success factors

- Focus on the process: moving away from the (intuitive) categorization of “super star” vs “under-performing” employees to asking what in the process is getting in the way of overall success.

- Evidence-based conclusions: not everyone – applicants, employees or management – was on board on Day 1, but the factual evidence supported common conclusions and constructive dialogue on what the team wants to do differently. Significantly, this was achieved by shifting the focus from “how do we do what we do?” (the current process) to “what do we want to achieve?” – i.e., “why are we doing this?” (‘job’ of the process).

- A genuine desire from all stakeholders to improve, moving away from a tendency to blame others and instead addressing problems as a common challenge

- Implementing “quick wins” early in order to sustain momentum, while at the same time developing detailed implementation plans for longer-term solutions

- “First followers”: it didn’t end on Day 5 of the workshop. Not only did the participants learn and actively apply what they learned in the workshop, they taught it to their colleagues when they got back to their desks. This exponentially increased the likelihood of success and promulgated the leanings throughout the organization.