Why is strategic planning so dreaded? How often do we actually deliver what the plan outlined? Why is buy-in so low? How many retreats are show-and-tell sessions instead of true strategic discussions? Why do we find ourselves at year-end, engaged in creative writing to provide the impression that we met our goals?

Some organizations have taken a different approach and are getting noticeably better results; here are five practices that have helped them improve.

1. Start with the problem

Planning retreats are often filled with solutions and pet projects. The easy way out is to say “yes” to them all, keeping peace in the family, while overloading people, wasting resources, and diluting focus. This happens when you start with the solution, instead of with the problem. Once a group agrees on a specific, measurable, client-focused problem to solve, then it takes much less effort to select and gain consensus on a solution.

We worked with an agency that pursued the solution of “consolidate our service desks” for over five years, with nothing to show for it but a recycled PowerPoint deck. When we asked them what problem they were trying to solve with this consolidation – most executives were vague, or could not identify a specific problem. Five years and millions of dollars of consultants’ fees wasted. Contrast this with a similar organization that identified a key problem as “74% of client contacts in 2012 were preventable. Impact: reduced ability to address value calls within 24 hours, creating unacceptable risk for our clients.” Which organization do you think made more progress, faster?

If you identify and agree on the problem and its impact, then choosing the solution becomes much easier. Einstein said: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” It feels slow to start with the problem and its causes, but as one corporate executive said, as she handed out a plush turtle to the participants of the planning retreat: “we have to move slow to go fast.”

2. Create Broader and Deeper Ownership

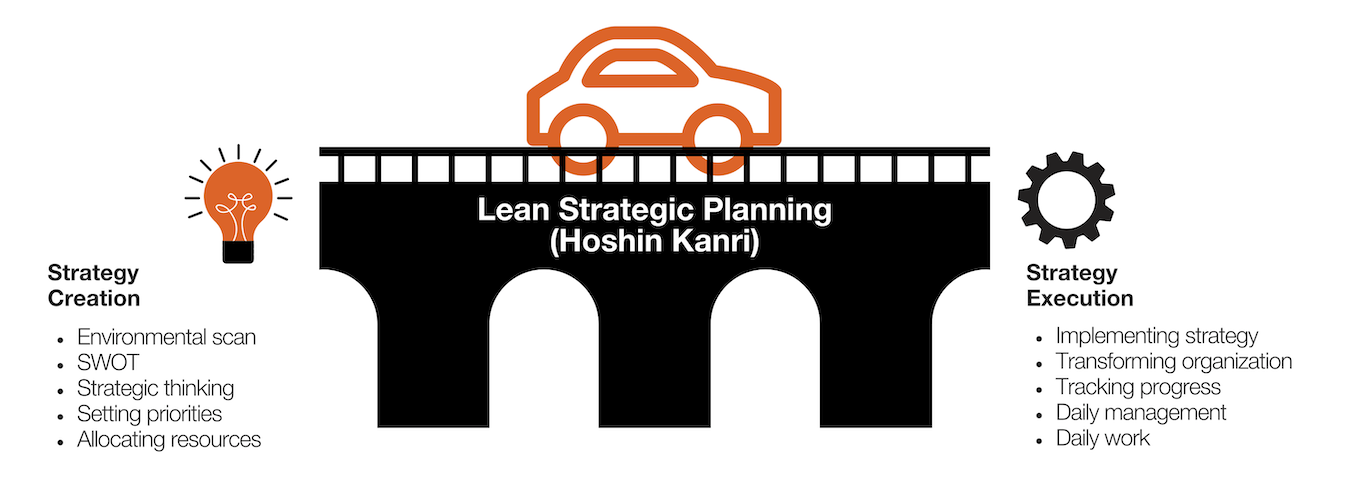

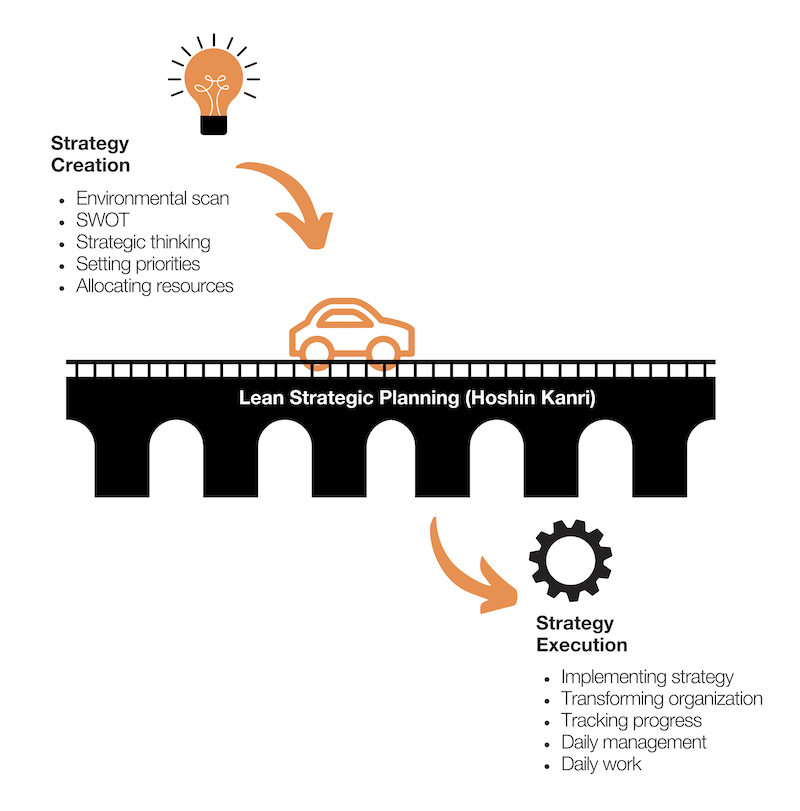

Many organizations treat strategy creation as separate from strategy execution: Senior executives, working with other executives, create the strategy, then hand it off to others to implement. This is a recipe for misunderstanding, misinterpretation and low buy-in. Lean Strategic Planning acts a bridge between the two, providing a methodical approach to set the strategy and a framework to follow through on execution as illustrated below.

We often spend immense effort creating strategy, and the remaining effort to sell the idea to staff. Execution is an afterthought – “we’ll let the operational people figure that out”. No wonder that Harvard Professor John Kotter found that 70% or more major projects fail to meet their initial objectives.

A better approach:

- At their retreat, executives identify on a single page: Point “A” and Point “B”, the strategic problems that must be solved along the way, causes, and, in rough-draft form, incomplete solutions.

- They then show their work to leaders across the organization, 2-3 levels below, and ask: “Did we get this right? If not, what do you see? Challenges?”

This is called “catchball” like two groups tossing a ball back and forth. Senior executives focus on the “Where we are going?” and “What are the gaps?” and the executors focus on “How can we get there?”. The benefits? A more-executable strategy with deeper ownership from the executors.

3. Make the plan visible and create routines

It is hard to manage what you cannot see. Strategic plans are often buried on the intranet or in binders. One corporation we worked with depicts its plan on whiteboards at multiple levels, from C-Suite to front line staff. Each level sees how it contributes to the top-level priority, they make regular adjustments, and, as they learn, performance improves. Once per quarter executives conduct what is called a “wall walk” to go, priority by priority, through their plan to troubleshoot and adjust as a group.

4. Recognize true capacity and say “No thanks, not yet” to what does not fit

We asked an ADM how many priorities his branch had this year. He replied proudly: “52”. We asked him if he could recite them. He paused, and sheepishly replied “no”. Given this, is it realistic for others in his branch to execute them all? With too many priorities, focus and effort is diluted and little gets done.

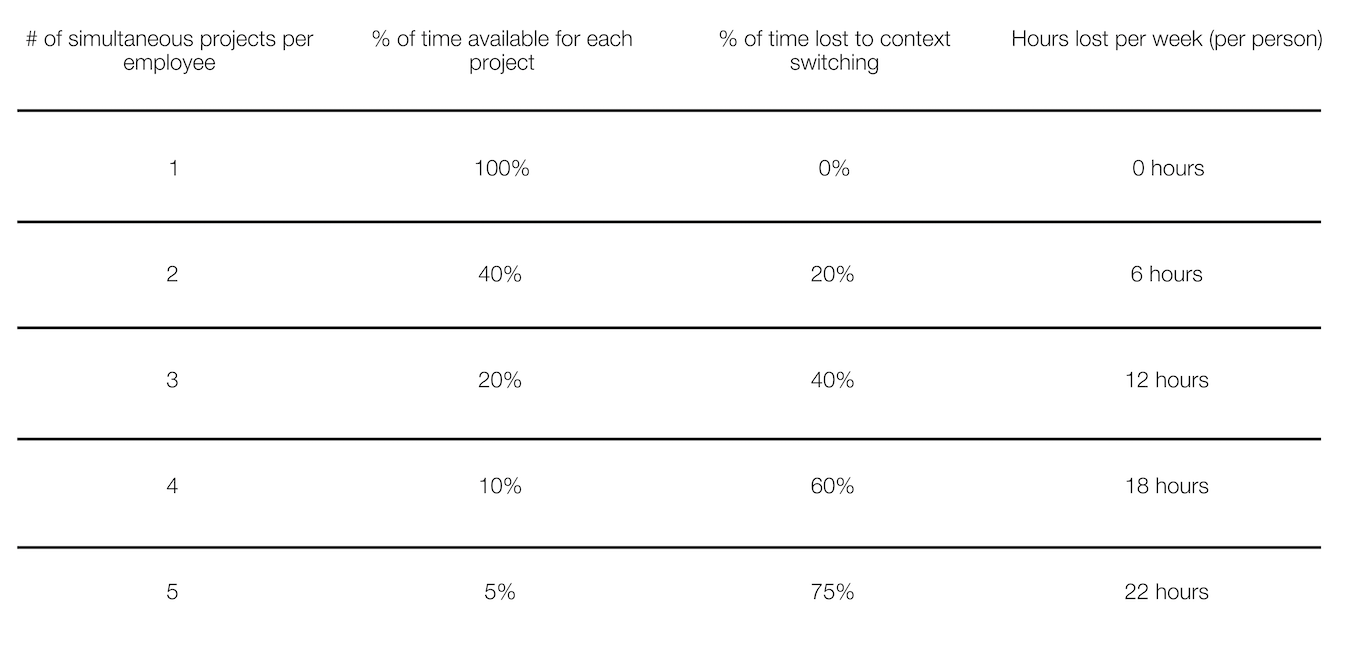

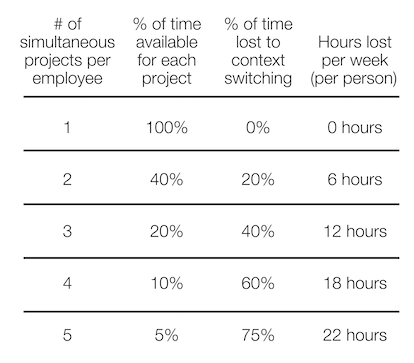

A study of software coders shows what happens when humans take on too much at once and switch between high-focus tasks (context switching), otherwise known as “switch-tasking".

How do you say “no” to less-important priorities so that you don’t fall prey to this capacity drain, without alienating stakeholders who may own these priorities? By starting with the problems to be solved, instead of starting with solutions, groups typically reduce priorities, and without hard feelings. Next, identify the “Must-do, can’t fail” / “Breakthrough” priorities, versus “Should-do”, “Could-do”, “Do next year” and “Don’t do” priorities.

Using a simple method to quantify available and required capacity, most organizations realize that they have been signing up for 100%-200% more than they realistically have capacity to execute. By identifying the capacity price tag of each potential priority, executives more quickly come to consensus on which to keep and which to defer or abandon – and also address many execution challenges.

How do you say “no” to less-important priorities so that you don’t fall prey to this capacity drain, without alienating stakeholders who may own these priorities? By starting with the problems to be solved, instead of starting with solutions, groups typically reduce priorities, and without hard feelings. Next, identify the “Must-do, can’t fail” / “Breakthrough” priorities, versus “Should-do”, “Could-do”, “Do next year” and “Don’t do” priorities.

Using a simple method to quantify available and required capacity, most organizations realize that they have been signing up for 100%-200% more than they realistically have capacity to execute. By identifying the capacity price tag of each potential priority, executives more quickly come to consensus on which to keep and which to defer or abandon – and also address many execution challenges.

5. Adjust as you go

A Ministry of Health was able to reduce its number of top-level priorities from over 30 to 18. A regulatory Commission reduced its priorities from over 20 to two. In both cases, they actually delivered on their priorities listed in the plan. Less overwhelmed, they were able to adjust along the way to deal with political and environment-driven change. A corporation used its quarterly review to re-assess capacity required, and where to redeploy capacity in order to focus on the most important priorities. Regular executive “wall-walks” are an efficient and effective way to check to stay on course, and to be nimble enough to adjust to unforeseen challenges and changes that will always be a part of public service. As a bonus, this sends a message of the importance of continuous improvement at all levels.

In this content area, we cover:

- What is Lean Strategic Planning and Deployment? How does it differ from traditional planning?

- Five shortcomings of traditional strategic planning

- Six stages of Lean Strategic Planning

- Developing a “North Star” to guide the strategy and operational decisions

- Identifying the “must-do, can’t fail” initiatives versus the “should-do, could-do” and “don’t-do” initiatives

- How to manage expectations of internal stakeholders when saying no.

- How to understand and manage capacity available and apply it to the “critical few” initiatives

- How to stabilize operations first to then free up more capacity to devote to strategic initiatives.

- An overview of Lean tools including: Strategy Maps, A3 Reports, Fishbone (Ishikawa) diagrams, X-Matrix, visual management

- How to design plans for ‘implement-ability” to improve results

- How to broaden ownership of the plan beyond the executive suite

- The important role of support functions (HR, IT, Finance, Admin., etc.) in the process

- How to use existing tools and templates (PAA, RPP, DPR) to apply the Lean approach – instead of reinventing the wheel

- How to execute this approach, including ongoing routines of Plan-Do-Check-Adjust to ensure that your organization continues to adjust during the year, learning and adjusting along the way

Rybing, T. (2014, October 12). Context Switching – Public Enemy No. 1?. https://theagileist.wordpress.com/2014/10/12/context-switching-public-enemy-no-1/

Weinberg, G.M. Quality Software Management: Vol. 1 System Thinking. New York. Dorset House, 1992. p. 284

McKeown, G. (2014). Essentialism: The disciplined pursuit of less (First Edition.). New York: Crown Business https://gregmckeown.com/book/